by By Carla McKirdy for Bust Magazine

If you’ve ever wondered what life in America would be like if the laws protecting a woman’s right to choose were reversed, look no further than Argentina.

Underground abortion clinics whose addresses are revealed only in hushed tones via word of mouth. The paralyzing fear of undergoing what should be a simple medical procedure, but is instead a life-threatening one, because an unlicensed doctor is performing it in unhygienic conditions. Friends and relatives resorting to dangerous folk traditions in an attempt to perform at-home abortions.

This is not just a stark premonition of what the U.S. could look like if anti-choice candidates get their way: it is the current reality in Argentina, a place where an unwanted pregnancy can easily become a death sentence. Despite some strides toward decriminalization-a 2012 Supreme Court ruling made abortion legal in cases of rape and was eventually expanded to include instances of incest or when the mother’s health is as risk-the procedure has been illegal in Argentina since their penal code was established in 1922. Regardless of it’s endurance in the bedrock of Argentine public policy, however, this law poses a serious threat to the physical and mental wellbeing of half the nation’s population-a group that continues to end unwanted pregnancies, generation after generation, by any means necessary.

Hannah, 28, a U.K. native, learned this the hard way, when she came to Argentina in 2013 to visit her boyfriend. Soon after, she found out she was pregnant and wanted to abort. She read up on lots of abortion information to try and learn more about the procedure before she went through with anything. Having an abortion is a big decision to make so it was important for Hannah to learn exactly what’s involved. In her native country, the procedure would have been a breeze: walk into a clinic, verify the pregnancy, get the RU-486 pill for free courtesy of the National Health Service, stay for observation while the pill takes effect, then go home. But in Argentina, it was a stressful ordeal exacerbated by lack of access to information, a language barrier, and the illegality of a procedure she had always taken for granted. “We went to a free sexual health clinic where they confirmed the pregnancy and we asked about abortion,” Hannah recalls.

At no point did I actually know if this doctor was a real doctor. The procedure had been done in an apartment. I didn’t see his credentials.

In Argentina, illegal abortion providers come in many shapes and forms-ask around long enough, and you’re sure to find someone who knows where to get one. The place Hannah went didn’t provide abortions on-site, but they knew where to send her. “We were given a prescription for all the different drugs and things they would need to perform a surgical procedure,” she says. “It was explained to us that a doctor cannot buy them without raising suspicions, so we had to buy them ourselves from different pharmacies.” Once they overcame that obstacle, their financial hurdle remained. “The total cost of everything, including the prescriptions and the procedure, was about $2,500,” Hannah explains. That’s a huge sum in Argentina, where the average yearly income per capita in 2013 was about $14,500.

“I was not allowed to eat and we were given an address on a scrap of paper,” Hannah recalls. “We went there and the place was literally an apartment, with the living room turned into a waiting room, and a bedroom that was made into a procedure room. We signed the paperwork and I went into the procedure room and lay down on the bed. They did a scan, and there on the screen was a little amniotic sac with a jellybean inside, a seven-week-old fetus. They gave me a sedative and the last thing I remember before drifting into unconsciousness was that image. I went to sleep crying. I woke up after the procedure and the first thing I saw was that screen. It was empty and so was I. I cried and cried. They took me back out to the waiting room and I sat on the sofa while the sedative wore off. I remember thinking I just need to leave, get out of this place. I cannot stay here a second longer. They said if I could walk backwards and forwards to the door twice without falling over, I could leave. I remember starting to walk, and although everything went black and I couldn’t see, I did it. I was so determined to leave. When we got out onto the street, I passed out. My boyfriend put me in a taxi and took me home. I do not remember that journey. At no point did I actually know if this doctor was a real doctor. The procedure had been done in an apartment. I didn’t see his credentials. I had no recourse for complaint if he had damaged me internally. At no point did I feel the care or compassion I would expect from medical professionals in the U.K. or elsewhere where it is a legal procedure.”

But it is a fact that many professional doctors in Argentina perform abortions. Though many keep this a hushed secret, and it does not make abortions any safer for the women involved. These doctors do not always use the same equipment and procedures a hospital would, and unlike in the US, one cannot easily access a medical malpractice lawyer, especially for something as forbidden as an abortion. Thus there is little incentive for the doctors to be professional, and there are few legal ramifications if the doctor chooses to ignore the duty of care they are meant to have towards their patients.

One common myth that continues to send women to the hospital–sometimes killing them or, in the best of cases, leaving them sterile-is the practice of inserting a sprig of parsley through the vagina and into the uterus to induce abortion.

At an average cost of $1,000 per procedure, a relatively safe illegal abortion like the one described earlier is a luxury only middle and upper-class women can afford. Meanwhile, low-income women who seek abortions are the ones who frequently pay for them with their lives. An estimated half a million illegal abortions are performed in Argentina every year. From these, 80,000 women end up hospitalized as a result of complications, and 100 of them die-making abortion the number-one cause of maternal death in the nation. Women who can’t afford pricey black-market clinics are typically relegated to dangerous back-alley abortions performed by untrained amateur physicians, and even sometimes by curanderos-traditional native healers who practice a combination of herbal medicine and ritual magic. In rural areas especially, women continue to fall prey to local lore and use risky homemade methods to induce an abortion.

One common myth that continues to send women to the hospital–sometimes killing them or, in the best of cases, leaving them sterile-is the practice of inserting a sprig of parsley through the vagina and into the uterus to induce abortion. What these women don’t know, explains Dr. Stella Manzano-a physician who cared for many such women while working in the northern provinces of the country-is that it’s not the parsley that causes an abortion, but the ensuing infection. Most uterine infections would induce an abortion. But they can also kill. As can abortions performed with knitting needles, wire hangers, and other household implements-methods many of Manzano’s patients tried before seeking her help.

After witnessing the very real horrors of at-home abortions and seeing too many women die trying to rid themselves of unwanted pregnancies, Dr. Manzano returned to her home province of Chubut to take the matter of abortion access into her own hands. She now chooses to interpret the law in her own way and offers free abortions-because health care in Argentina is free-at the hospital that employs her in Patagonia, which draws hundreds of women who often embark on long pilgrimages to obtain her services. Manzano, today in her mid-50s, gained local notoriety with her first abortion patient: a 15-year-old girl who had been raped. None of her colleagues wanted to step up to the plate, so she went ahead and performed the procedure herself. And she hasn’t stopped since, using broad definitions of what constitutes “a risk to the mother’s health” to act within the confines of Argentine law.

The procedures Dr. Manzano performs fall within a grey area between legal and black market. Abortion is still illegal, but according to provincial legislation where Manzano practices, it is not punishable by law since she has deemed every pregnancy she’s ended “a risk to the mother’s mental health.” While this loophole has so far kept Manzano in the clear, many of her colleagues refuse to follow suit for fear of being shunned by their more conservative peers. But Dr. Manzano simply doesn’t care about her social standing within the medical community. “I’m proud to offer this service,” she says. “I even have a poster up in my office at the hospital that reads, ‘Here we provide safe and legal abortions.'”

Small private clinics also stretch or break the law in the interest of the greater good, such as the one run by Doctor German Cardoso in Tandil, in the province of Buenos Aires. “I employ the latest procedures and have trained extensively with doctors abroad,” he proudly explains. “This is not always the case with illicit abortion clinics.” Dr. Cardoso, 58, obviously takes his job seriously. He became a surgeon in 1984. But he didn’t get into the abortion business until 2000, when a nurse from a neighboring town came to him begging him to perform an abortion on her. A single mother with several small children, she could not have another baby. He agreed, and bolstered by word of mouth, he became his region’s leading abortion provider.

Dr. Cardoso is no stranger to prosecution. He’s been taken into police custody twice. And the media has largely vilified him, dubbing him “Dr. Abortion.” Yet, due to a technicality, no charges have ever been filed against him. In order to legally accuse someone of being an abortion doctor, he or she would have to literally be caught extracting a fetus from a woman’s uterus. Circumstantial evidence and hearsay are not good enough, and so for now, Dr. Cardoso remains a free man. When answering questions about his legally ambiguous enterprise, Cardoso is open and tells it like it is. “There is a lot of money in the abortion business,” he admits. But after seeing plenty of quacks and instances of birth injury results from malpractice, he says there is nothing he would like more than to see abortion legalized and provided for free at public hospitals.

Her clinic admitted patients for “IUD insertions.” Patients left the clinic a few hours later, no longer pregnant, with an IUD and a hefty bill.

Legalization would certainly have made a difference for Camila Gónzalez, who was only 18 when she found out she was pregnant. “My world came crashing down,” she recalls now, at 22. “I come from a background in which I was always told that getting pregnant would be the worst thing that I could ever do to my family.” Gónzalez knew what she wanted to do, but had no idea how to go about it safely. She confided in her boyfriend’s mother, who quickly pointed out a neighborhood clinic that she’d heard “took care of such problems.” This particular place was an illegal abortion clinic masquerading as a gynecological practice, but in many respects, Gónzalez was fortunate. Her clinic was an actual medical facility staffed with trained doctors who admitted patients for “IUD insertions.” Patients left the clinic a few hours later, no longer pregnant, with an IUD and a hefty bill.

Just because Gónzalez’s abortion was more professional than most, however, does not mean the experience was easy. “I was treated like shit after the procedure,” she says. “I had been sedated, so when they wheeled me out, I thought they hadn’t performed the abortion. I was horribly confused. I didn’t know if I was asleep, awake, if they had done it or not. They lay me on a stretcher to rest, but there was a document missing. I don’t know if it was my birth certificate they needed or my mother’s signature-I was 18 but I needed a parent’s signature until age 21. It’s just nuts. [They needed paperwork] to protect themselves in case something went wrong with my ‘IUD insertion.’ I don’t know what was missing. But this woman comes up to me and starts screeching, ‘You didn’t turn in this document!’ I had just been wheeled out! I was still under anesthesia. I told her, ‘I dunno, look, my boyfriend is outside. Go ask him for the documents. I don’t know…I’m still drowsy.’ But to this day, I’m still so angry at that woman. How could she treat me like that after what I had gone through just five minutes before?”

To avoid the disorientation and discomfort Gónzalez describes, Internet savvy women in Argentina are now spreading the word about a free app created by the feminist group Women On Waves called Safe Abortion With Pills. It explains to users what the laws are in their country concerning abortion, tells them in their own language how to perform an abortion with pills, and highlights local organizations they can contact to get support-and the pill itself. Medical jargon can be confusing, especially if it’s in another language, so it’s crucial that this resource is designed appropriately for the women using it. It’s likely that the feminist group used a medical translation company to ensure all information and instructions were clearly laid out to avoid any injury or miscommunication. But once again, since this is a tool that requires Internet access, which not everyone has but if just one woman was able to read this information and spread it, far fewer women would be left in the dark, although it would be much easier if more women had access to the internet.

That’s where consejerias, or counseling centers, come in. These informal service bodies backed by the World Health Organization reach women in need through email, telephone hotlines, social media, and even with posters and graffiti on the streets. Juliana, a young Argentine woman who prefers to remain anonymous, went to a counseling center when she decided to abort. “They helped me get the pills, and even offered to stay with me while I took them and waited,” she recalls. “But I preferred to do it alone, so they gave me the instructions and let me be, which I appreciated.”

But there’s a wrinkle. Marcela Brusa, one of the leaders of The National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortions (Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito)-Argentina’s most prominent pro-choice organization-points out a flaw with these counseling centers. “Activists have undertaken the creation of counseling centers as a form of resistance,” she says. “But accepting the existence of these centers, to a certain extent, feeds their status as something semi-legal, when they should be completely open and legal.” Brusa points out that medical professionals do not vet the information disseminated through counseling centers, and even if the volunteers have the best intentions, most are not trained doctors. In their desire to see women access their right to abortion, counselors could disseminate information that might prove detrimental to a patient’s health.

Now in her 60s, Brusa says pro-choice activism has been very much alive in Argentina since the 1970s-although she wasn’t in the country when the first agitators began to organize. Brusa fled in the late ’70s, when an Argentine military dictatorship took control. Thousands of people were disappearing without a trace, taken by military forces and never seen again. The new government’s main targets were students and intellectuals, or as the de-facto government referred to them, “political dissidents.” Brusa escaped this reign of terror by migrating to the U.S. where she furthered her studies and obtained her PhD. She continued supporting causes close to her heart while she built a new life in Texas, and became a counselor at an abortion clinic.

Little did she know, however, that the persecution she was fleeing was about to catch up with her in a different way. While working as a counselor helping women make reproductive decisions and accompanying patients during procedures, she found herself in the crosshairs of American anti-abortion violence. Break-ins at her clinic were common, protesters outside her workplace harassed both Brusa and her patients, and she was stalked and regularly received telephone threats. She held her ground, though, and actively participated in the pro-choice movement until she returned to her native Argentina later in life.

Brusa’s decades of experience working in abortion clinics has come in handy now that she’s back in Argentina. And the last thing she wants for her home country is another Roe v. Wade. “The [problem] in America is that Roe can be reversed, depending on the ideological makeup of the Supreme Court,” she explains. It’s true-abortion legalized through case law can be constantly chipped away at with undue burdens to clinic access, and the U.S. is a prime example of what it’s like to wage a constant battle to protect any advancements in reproductive justice. To avoid these issues, the aim of the National Campaign in Argentina is to have abortion fully legalized by law, so that the procedure may be performed for free at public hospitals. Once it becomes nationalized public policy, legalized abortion would be very hard to overturn. “To have the right to abortion backed up by a law means that it would be more difficult to erode that right,” explains Brusa.

Under the military government, pregnant dissidents were cared for until they gave birth. Once a captive woman gave birth, she was disposed of.

Victoria Donda, a member of the Argentinean equivalent of the House of Representatives, agrees. At 38, the lawmaker has just started her third consecutive term in office. And her recent re-election speaks to the rising popularity of her platform issues-legalizing abortion and safeguarding basic human rights. Donda had first-hand experience with the latter as a victim of the military dictatorship. She was born in 1977, inside of a clandestine detention center. Her parents had been kidnapped and, promptly after her birth, they were both “disappeared” (code for murdered). As a baby, she was given away to another family. But eventually, she discovered her true identity and was reunited with her extended biological family.

The systematic “disappearance” of people like Donda’s parents was common between 1977 and 1983. And although no mercy was shown for most political prisoners-many were sedated and thrown into the Atlantic Ocean from planes on what came to be known as “death flights”-pregnant dissidents were cared for until they gave birth because the military government was staunchly Catholic and anti-abortion. Under their rule, once a captive woman gave birth, she was disposed of. And this is exactly the type of attitude toward women that Donda is battling today in Congress. Like her birth parents before her, she wants to forge a more just and equal society; and to Donda, legalizing abortion is just part of the package. “The Church has really influenced the [abortion] debate in Argentina,” she says. “But I think the issue at stake now is how the State regards women’s bodies.”

Although the country’s Christian roots were long blamed for its steadfast opposition to women’s reproductive rights, in 2010, Argentina became the first Latin American country to legalize same-sex marriage. Yet Argentina and its regional counterparts continue to have the most restrictive reproductive health policies in the world, with a few exceptions; in Cuba, some Mexican districts, and in neighboring Uruguay, abortion is legal and accessible free of charge at public hospitals. Other countries in the region, however, are even stricter. Chile, for example, upholds anti-abortion legislation dating back to 1874 that makes the procedure illegal unless performed to save the mother’s life. Just last month, Chilean activists opened up a national debate that could help the country take the first steps toward legalizing abortion in cases of rape or incest, but they still have a long way to go.

Further along on their quest for legalization, Argentina’s pro-choice activists are increasingly using social media to get their message out. Brusa herself is the force behind a Facebook group that distributes information about abortion in Argentina, and she receives counseling requests via private message on a daily basis. “I ask a few questions and divert their concerns to a person I think can help,” she says. “There are avoidable and unavoidable abortions. We try to avoid the avoidables. But if a woman does not want to have a child, then that abortion is inherently unavoidable.” Hopefully, the Argentinean government will one day recognize reproductive rights as human rights and take abortions out of the shadows and into hospitals where they belong. In the meantime, the nation’s pro-choice activists like Brusa and Donda are watching the U.S. struggle closely-and learning from America’s mistakes.

—

By Carla McKirdy

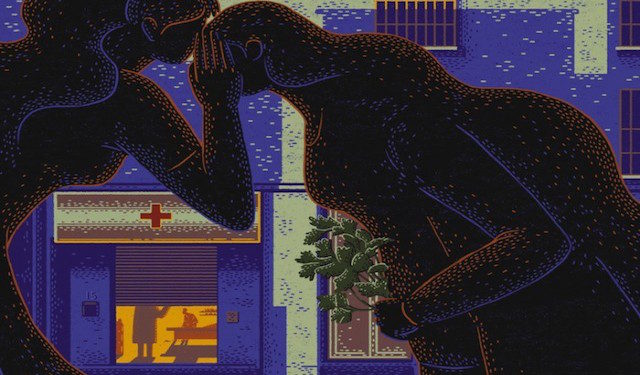

Illustration by Yukai Du