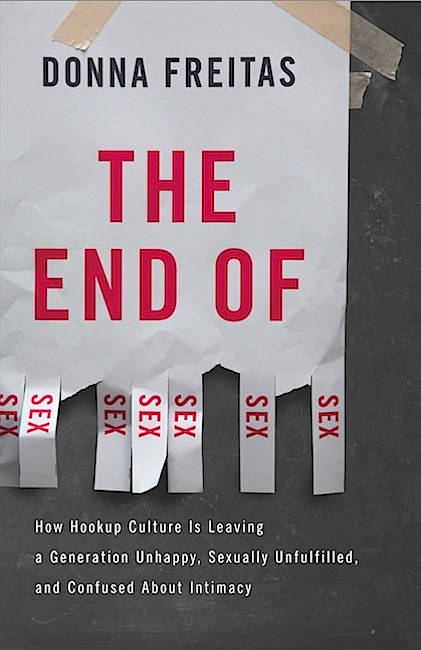

The End of Sex by Donna Frietas is getting a lot of action lately, with reviews calling it “important, wise, and brave” (The Atlantic), “illuminating” (WSJ), “straight-forward, well-researched, and eye-opening” (Publishers Weekly), and with Frietas herself penning an editorial for the Washington Post and nabbing a coveted spot on The Today Show. Subtitled “How Hookup Culture Is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Sexual Intimacy,” the book analyzes 2,500 surveys from 11 colleges and finds that casual sex is perceived by students as the only romantic option on campus these days — and that actually bums a majority of them out. Here’s an excerpt:

The Second Shift of College

Amid the seemingly endless partying on America’s college campuses lies a thick layer of melancholy, insecurity, and isolation that no one can seem to shake. College students have perfected an air of bravado about hookup culture, though a great many of them privately wish for a world of romance and dating. And yet they soldier on. By all appearances, graduating college with sex on one’s social resumé is as important as it is to have a range of activities, internship experiences, and a solid GPA on the professional one. In today’s college culture, sex is something students fit into their schedules, like studying and going to the gym.

College students learn from the media, their friends, and even their parents that it’s not sensible to have long-term relationships in college. College is a special time in life—they will never get the chance to learn so much, meet so many people, or have as much fun again. Relationships restrict freedom—they require more care, upkeep, and time than anyone can afford to give during this exciting period between adolescence and adulthood. They add pressure to the already heavily pressured, over scheduled lives of today’s students, who, ac- cording to this ethos, should be focusing on their classes, their job prospects, and the opportunity to party as wildly as they can manage. Hookups allow students to get sex onto the college CV without adding any additional burdens, ensuring that they don’t miss out on the all-American, crazy college experience they feel they must have. They can always settle down later.

Students play their parts—the sex-crazed frat boy, the promiscuous, lusty coed—and they play them well. But all too often they enact these highly gendered roles for one another because they have been taught to believe that hookup culture is normal, that everyone is enjoying it, and that there is something wrong with them if they don’t enjoy it, too. What could be better than sex without strings? Yet, in fact, many of them—both men and women—are not enjoying it at all.

Hookup sex is fast, uncaring, unthinking, and perfunctory. Hookup culture promotes bad sex, boring sex, drunken sex you don’t remember, sex you could care less about, sex where desire is absent, sex that you have “just because everyone else is, too,” or that “just happens.” It’s the new, second shift of college: the housework, the domestic labor that everyone needs to pitch in and get through because it simply has to get done. The more students talk about hooking up, the clearer it becomes that it has less to do with excitement or even attraction than with checking a box off a long list of tasks, like homework or laundry. And while hookup sex is supposed to come with no strings attached, it nonetheless creates an enormous amount of stress and drama among participants.

Today’s younger generation learns quickly and learns well that the norm is to be casual about sex—even though so many of them don’t fit this “norm.” Parents and educational institutions unwittingly promote this idea. Because we worry about the perils of casual sex among teens—unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and, for some constituencies, sin and God’s disapproval—the very people who should be mentoring young men and women about the pleasures and joys of good sex instead focus on its dangers. Sex education in high schools, in both its comprehensive and abstinence-only forms, tends to favor the how-to’s or the why-not-to’s of sex. This limited approach is often reiterated in first-year college orientations, which tend to concentrate on birth control, STIs, and sexual assault. Rather than empowering teens and young adults to make informed decisions about sex, these sex-educational methods often reinforce the idea that hookup culture is the norm, that everyone is doing it, and that all students can do is protect themselves against its worst excesses.

The average college student, like the average adult, wants to have a meaningful sex life, even a soulful one, even if that requires having less sex or, for a time, no sex. But the path toward this goal is dimly lit. This leaves students fumbling all the way up to their senior year, sensing that something is missing from their lives, yet with no idea how to find fulfillment or who can help them in their search for it. Universities may be doing a good enough job facilitating safe sex for those who genuinely enjoy hooking up. But many students today are graduating college either unhappy or ambivalent about their sex lives, and unable to imagine a more fulfilling alternative. At the center of their unease is the four years they’ve lived within hookup culture.

Hookups have existed throughout human history, of course, but what is now happening on American campuses is something different. College has gone from being a place where hookups happened to a place where hookup culture dominates student attitudes about all forms of intimacy. The hookup has become normative, and hookup culture a monolithic culture from which students find little chance of escape. It is the defining aspect of social life on many campuses; to reject it is to relegate oneself to the sidelines of college experience.

In my personal experience as a university student in the early to mid-1990s, the hookup was one of many available forms of relating. Hookup culture was like a town everyone knew about and knew how to find. We also knew who lived there permanently and partied there exclusively. Most of us would visit hookup culture and its accompanying parties a number of times during college, if only to see what it was like. But we weren’t immersed in it throughout our four years—or, at least, we didn’t have to be if we didn’t want to. The landscape for navigating one’s romantic and sexual life was much broader and more diverse and included traditional dates and long-term romantic relationships as well as hooking up. (There was also the possibility of opting out of all of it.) But even in the mid-1990s, hooking up could still mean making out at a party and exchanging phone numbers, with the thought of turning the make-out session into an opportunity for a relationship. It didn’t necessarily ride on the notion of unattached intimacy both during and afterward, and it wasn’t an end in itself.

Between 1997 and 2003, I lived on campus as a professional in student affairs departments at two major universities, one Catholic and one private-secular. More than anything else, student alcohol abuse was the major issue. My colleagues and I dealt with it on a regular basis with the students in our residence halls. Hookup culture existed then, too, but it didn’t dominate the social lives of students the way it does now. I witnessed couples heading out on dates, knew of long-term relationships that were kindled early on in a student’s first year of college, and listened as students chatted about their various social exploits and romantic aspirations. It wasn’t until my last few years living in the halls that student behavior became more extreme, and the drunken hookups more obvious because they began in the hallways, stairwells, and elevators in my building. But still, among the students with whom I came into contact for all sorts of student-affairs department reasons, conversation about hooking up was fairly minimal. You might hear the term once in a while, but it was not the thing that everyone was talking about constantly. Today, it’s almost the only thing.

One can only speculate as to the reasons that hookup culture has come to dominate college campuses in the early part of the twenty-first century. During the 1980s and 1990s, the threat of AIDS loomed over all sexual encounters. Today’s generation has a difficult time understanding the threat of AIDS, given advances in research and medication. The widespread availability and social acceptance of pornography is yet another factor that may contribute to the rise of hookup culture over the past decade. The ubiquitousness of pornography is changing the attitudes of young adults about sex, their expectations for their partners, and their understanding of desire, gender identity, and how one enters into various types of sexual intimacy.

Moreover, the campus culture—along with the wider culture—has become more superficial with the advance of technology. A frenetic go-go-go and do-do-do pace, increasing in the midst of an economic recession, has put young adults under ever more pressure. They are competing with each other for fewer and fewer jobs, but burdened with greater and greater expectations of success. Such pressure can breed stress, anxiety, and even selfishness, all of which are aided and abetted by technologies that allow us to text rather than call, and to interact superficially and efficiently, with broad swaths of “friends” and followers, through Facebook and Twitter, rather than engage in meaningful interactions face to face with other human beings. This pace and pressure coincide with the attitudes toward others fostered by hookup culture. Rather than looking at the people right in front of us, we look at our phones, preferring to touch a screen rather than the hand of a partner. Instead of engaging in conversation with those sitting next to us, we text, email, and chat with people nowhere near our bodies. We have become more excited about interacting with the various technological devices at our disposal than about developing relationships with real people, even our own children. This prioritizing of technology over in-person interactions does not teach us how to value the life and body of another human being, or what it means to treat others with dignity and respect. Instead, it promotes the idea that in-person relationships are cumbersome and time consuming—better to be dealt with on- line, or, even better, not at all.

Excerpted with permission from The End of Sex: How Hookup Culture Is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Intimacy, by Donna Freitas. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2013.

Interesting. Thanks for posting the excerpt. Most of what I’ve read about this book has dismissed it as slut-shaming nonsense, and based on this passage, that is not quite right. I think she’s working from assumptions, but she does have a couple of points.