Our friend Celia Bland, who works at The Bard Institute for Writing and Thinking, just down the road from us, recently published a book of poetry called Madonna Comix. It’s a large-format, fine art book that was a cross-country collaboration with the artist Dianne Kornberg; the poems feature the Virgin Mary in various modern-day incarnations: vending machine, bomber, girl going to prom, etc. (With a foreword by Luc Sante, another neighbor of ours up here in the Hudson Valley. Because we’re not the only creative types to have forsaken New York City, though we’re pretty sure we’re the only sex writers in our country bumpkin zip code — reason enough to move here, we suppose.) A few months back, we wrote this about Mark Bibbins‘ new book of poetry, They Don’t Kill You Because They’re Hungry, They Kill You Because They’re Full: “He will convince you poets are sexy and dreamy and powerful and relevant.” We’re happy to have further proof now in the Madonna Comix.

Immediately below is a short essay by Celia on her project and why she was drawn to the Virgin Mary — and what the Madonna means to her as a modern woman (and as a poet who “kind of specializes in poems about sex,” she says). Just below that, after the jump, we are thrilled to publish three poems and three illustrations from the book:

The Madonna Comix were originally Captions for Cartoons Not Yet Drawn. I imagined the poems’ stanzas appearing as comic strip captions beneath empty boxes – the panels drawn with different thicknesses of line but always empty.

The poems, you see, were about emptiness – a metaphorical emptiness as concrete as the air space where the Twin Towers once stood. I’d worked as a temp in Tower B and at noon every day that summer, I’d sat in the shadows of a desolate wind-swept plaza eating peanut butter sandwiches and hating my life. Looking back at my internal emptiness, so unaware of how the world could and would soon change, my complaints seem so petty, so personal. The poems written afterwards stung with self-rebuke, a kind of loss focused on my ideas of Mary, mother of Jesus.

Despite the poems’ sometimes smart-alec-y lines, I remain deeply moved by the Blessed Mother. I see her bereft at the foot of the cross, palms up in a gesture of acceptance, as in my poem “Education of the Virgin.” Mary breaks my heart. She does not rail against fate – Why hast thou forsaken me? She has the patient heaviness of pregnant women – that almost-bewildered delaying of self for another day, another day, before blessed release. I see her as a kind of shape-shifting superhero.

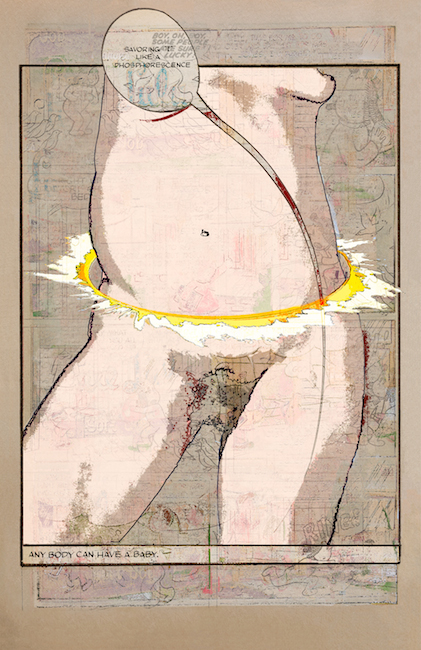

I wrote these poems in short lines and with some sense of the many roles women play: pregnant and scared, birthing and scared, mothering and resentful, joyous, bored, nurturing and self-abnegating. A woman who fell at the foot of the cross, beneath the corpse of her son, in a dead faint. A woman pressed into service. A vending machine for babies. A figure of maternal longing and infinite pity.

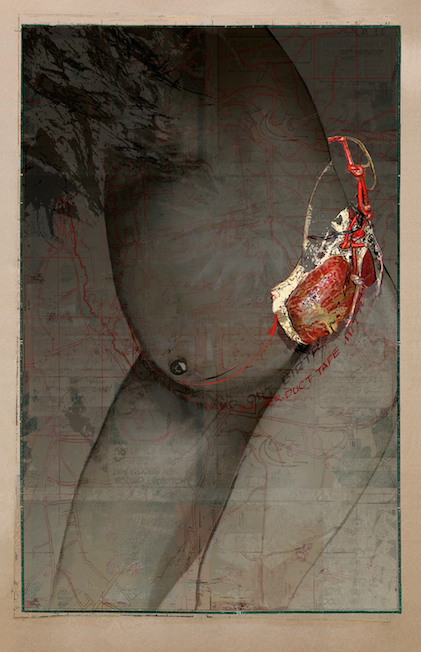

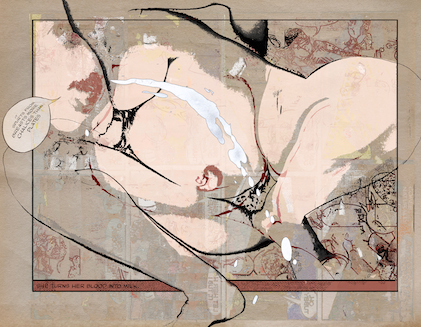

One day, wandering into an exhibition of text-inspired images at the Chicago Cultural Center, I saw Arachne, a collaboration between artist Dianne Kornberg and poet Elizabeth Frost, I decided that, yes, perhaps my poems could be captions for cartoons drawn. So I mailed her a series of poems about the Madonna—Mary as pelican, as bomber, as vending machine, as bereaved mother. Dianne responded enthusiastically to my ideas. She found some black and white negatives of photos she’d taken years before of a dancer seven months pregnant. These became the basis for Madonna Comix. Little Lulu bleeds through, a pentimento. The comic balloons for exclamations and jokey asides suggest the strange teardrop wombs that enclose medieval Madonna’s.

None of this is solely my invention, of course. Mary has always been, in the words of British historian Helen Hackett, a repository of “contradictory impulses towards the female body, including desire, fear, idealization and prurient fascination…” Pray to her to advocate for us lowly mortals, to intercede with a distant god. Always, when the Catholic missionaries came to a place, they supplanted the fertility goddesses, the Venuses of that place, with a Mary fashioned of clay and magic. This virgin, chosen by god, impregnated by him, not in Zeus’s golden shower or in the shape of a satyr or a husband, but by a white bird, bearing a word: that is, the word made flesh.

Making Mary, in my own mind, at least, most especially the protector of those laborers of the word.

Madonna of the Cigarette Machine

Drop your pocket change into my slot.

Modulated by slim levers and a semi-colon

soft packets – one

two three –

slip along my galvanized trough

once you pull these yellowing knobs.

A simple mechanism, yes, but

Ka-ching!

miraculous this

sweet contraction and

release

and a book of matches.

Education of the Virgin

Virgin Mary has never ventured

to the caves of Texas

where bats – little shudders –

breed like bad memories.

She has none,

you know, no packed bags

at the Union Station

where bats press themselves flat

against the peeling ceiling.

No shuddering regrets electrify

her epidermis like the flit of

a donkey’s ear.

This defines her innocence:

the sadness she feels for souls

consigned to places always cold

where the only lights are those

flickers of conscience

we bring with us.

She did it only once and that

was a Eucharistic moment,

the apotheosis of grace,

as if her womb were lined

with Communion wafers.

It’s God the Father, the Son, and the

Holy Spirit

in there, swallowed, perhaps, and

passed, with a kiss,

through nether lips.

Virgin Mary never goes where she is unwanted.

She bows her head to the ecstatic

eradicators, tribe haters, sex haters,

haters of the poor.

If her hovel is bulldozed, she has a cousin

in Babylonia — although moving, for Virgin Mary,

predicates cosmological occurrences, avian messengers –

and then there are the tickets

and checkpoints.

She turns her palms to the heavens.

A fine dust collects.

Life was a book Virgin Mary conned

until that death so public,

sap dripping along his legs slow

as the delineation of error from justice.

Getting down the body, unhooking his hands

like drapes from a rod —

only to stop a hole.

Madonna of Materialism

Should I be good?

I am cane sugar crystallized

on the papillae of the American idiom – no ideas,

longing for things.

No one has provided me with

courage or a station wagon.

When I was little

I wanted a two-car

garage I could leap from

and a trampoline.

I have settled like a porch,

like a belly, like sponge cake.

Should I go bad?

Go out for milk and bacon

at a bodega

in Nicaragua –

anywhere

beyond these borders?