Cory Silverberg is elevating in-home sex-ed to an art form, one kick-ass book at a time. His first kids’ book on reproduction, called WHAT MAKES A BABY (for preschoolers through 2nd-graders), combines inclusive language, helpful descriptions, and bright, bold and beautiful illustrations by Fiona Smyth (that get us all nostalgic for “Free to Be You and Me“) to answer the eternal kid question, Where do babies come from? What makes this first book so special is how all kinds of families are included in the answer. (We’ve given it as a new-parent present to hetero couples, gay couples, and a single mom who opted for sperm donation — all were appreciative of Silverberg’s modern, thoughtful approach.)

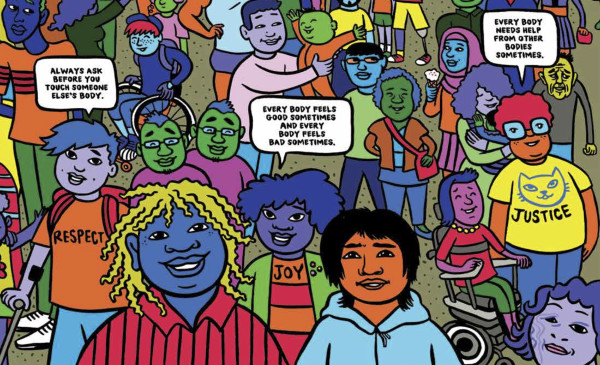

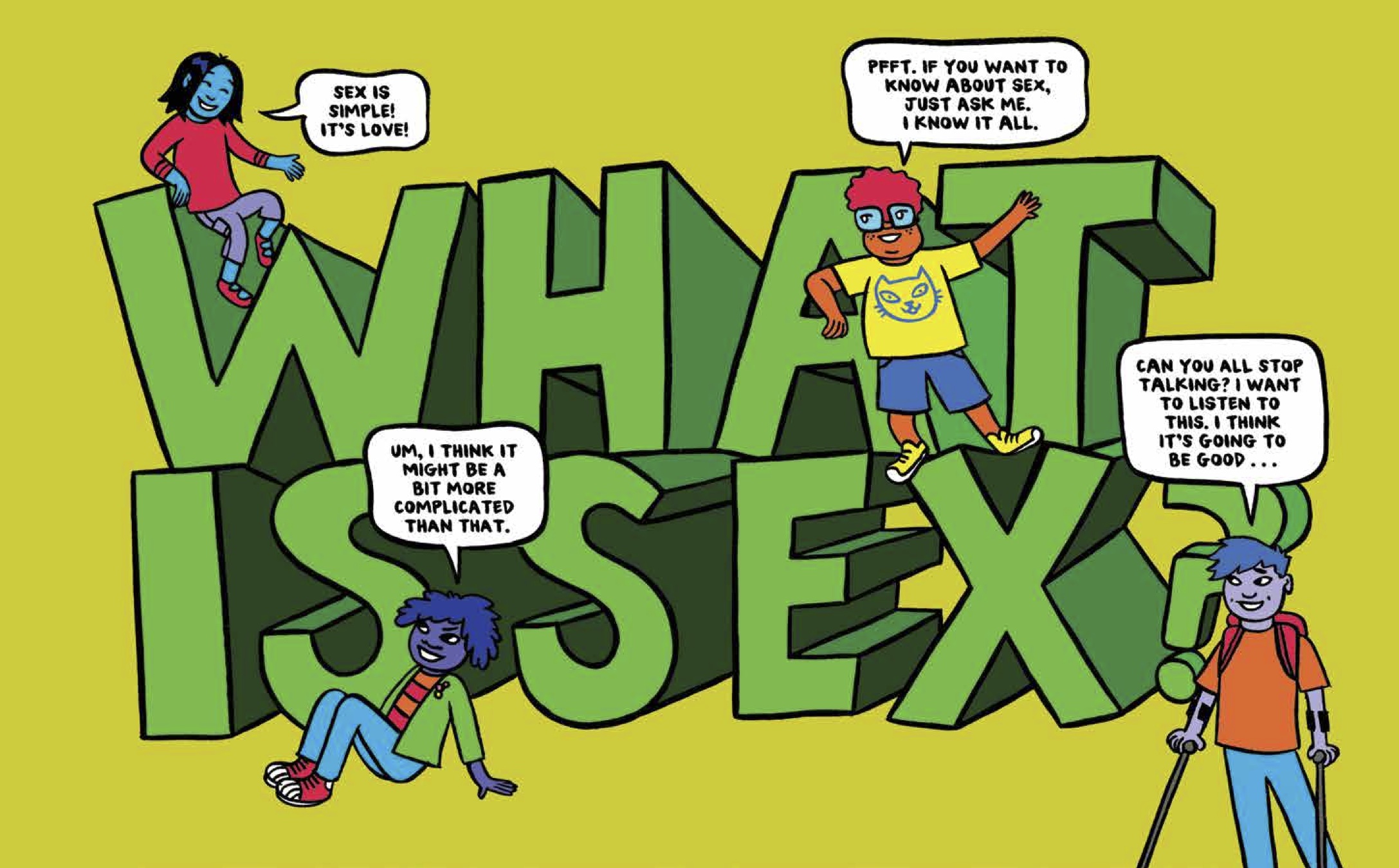

Now, his second book in the three-part series has just come out: SEX IS A FUNNY WORD: A Book About Bodies, Feelings, and You is a resource for kids ages 7 through 10 (and their parents/caregivers) about bodies, gender and sexuality, in comic book form — again, with Smyth’s signature illustrations. It delivers on its promise to open up “conversations between young people and their caregivers in a way that allows adults to convey their values and beliefs while providing information about boundaries, safety, and joy.” (Okay, maybe not if your values and beliefs are akin to those of the zealot mom from Carrie.)

Now, his second book in the three-part series has just come out: SEX IS A FUNNY WORD: A Book About Bodies, Feelings, and You is a resource for kids ages 7 through 10 (and their parents/caregivers) about bodies, gender and sexuality, in comic book form — again, with Smyth’s signature illustrations. It delivers on its promise to open up “conversations between young people and their caregivers in a way that allows adults to convey their values and beliefs while providing information about boundaries, safety, and joy.” (Okay, maybe not if your values and beliefs are akin to those of the zealot mom from Carrie.)

Luckily for us, Cory’s books have been published in sync with the ages of our eldest kids — so we expect (and anxiously await) his third book in the series, the one for pre-teens and teens, to hit shelves right around the time puberty strikes our own households. In the meantime, we wanted to talk more with Cory about some of the language used in Sex Is a Funny Word — the terms and phrases we agree every caregiver of a little kid should have in their vocabulary:

1. “Middle Parts”

Rather than “private parts,” the book recommends the phrase “middle parts.” Which begs the question, What’s so bad about “private parts”? Cory explains that it’s a euphemistic solution for little kids that doesn’t really work when we grow up. “When adults use the term they are only talking about genitals,” says Cory. “But any part of our body could be private. This is true in both religious/cultural contexts but also from a body empowerment perspective. So it just doesn’t make sense to say that breasts are a private part but the underarm isn’t.”

“Private parts” is also problematic from a harm prevention perspective: “Not all sexual abuse of children is focused on the genitals. When we teach kids that the only part of their bodies that are private and need protection are their genitals we are not teaching them the body awareness they need to help protect themselves from sexual predators.”

So Cory went in search of an alternative — one that dropped the euphemisms and was as honest as possible. And if you’re talking about the region from the chest to the crotch, what’s more accurate (and, in our opinion, more adorable) than “in the middle”?

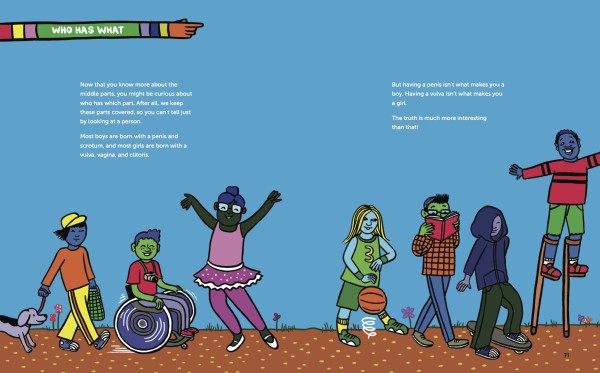

2. “Vulva,” et al

Confusing the vulva (the external female genitalia) with the vagina (the internal canal) is one of our pet peeves. We get why kids might do it, but adults? Who are having sex? In this day and age? With the Internet at their fingertips? Even sex education manuals use “vagina” incorrectly, which drives us — and Cory — nuts!

“Many of us parents don’t even know there is a difference between the vagina and vulva, so we use the word incorrectly partly because we don’t know better,” explains Cory. “Also, words like ‘anus’ and ‘clitoris‘ are just so foreign to most of us and so it feels weird to use them with kids because it feels weird to use them period.”

Another problem is the fact that so many adults automatically equate correct anatomical terms with sex: “Some of us only use a word like clitoris in a sexual context. I’ve definitely had parents feel icky about the word clitoris because they think it’s somehow too sexual. Of course it isn’t. It’s just the name of another body part.”

Cory likes to point out to parents that little kids don’t have these hangups or even an understanding of how words have sexual connotations. “So,” he says, “it’s an opportunity to work on our own anxiety and shame and to not pass it on to our kids.”

3. “Helpful & Hurtful Words” (as Opposed to “Good & Bad Words”)

In Sex Is a Funny Word, Cory writes that “words are not good or bad…The same word can feel good, or bad, or like nothing at all. It depends on who is saying it, how they say it, and why.” While it’s clear in the book that Cory is NOT advocating kids saying whatever the hell they want, we could see strict parents who are totally against any kind of swearing in any situation taking issue with the idea that there are “no bad words.” So we asked Cory how to make the case to them:

“The short answer for those parents is that they should be honest with their kids and say ‘I don’t want you using that language because it upsets me, it hurts my feelings.'” This way, the boundaries are set regarding certain words, while the emphasis is placed on the hurt feelings caused by those words when used in a particular context.

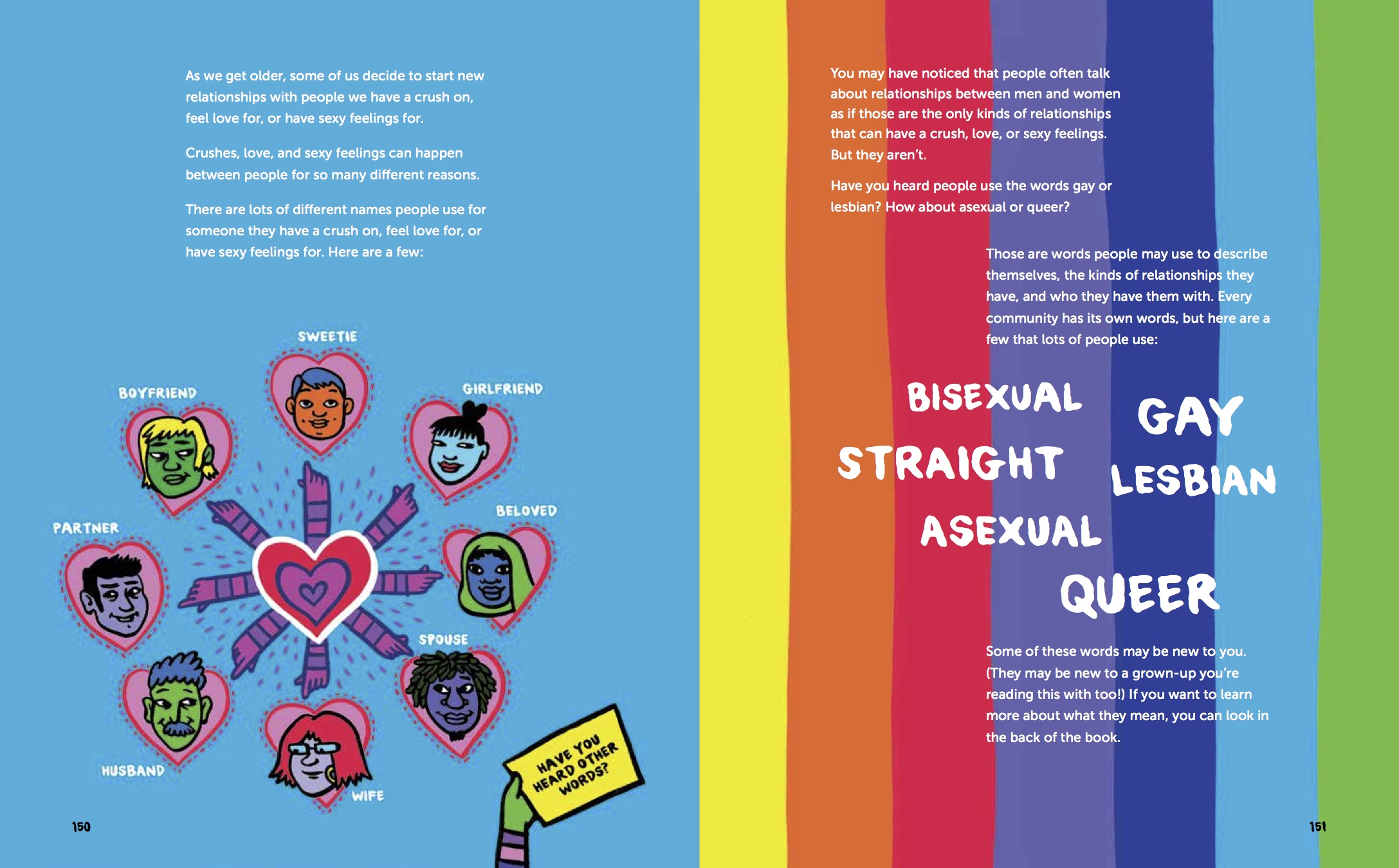

Cory adds, “What happens when we teach our kid that a word is bad, and then they hear it or see it in a different context, where it isn’t bad? Take a word like queer. I’m a queer person, it’s a word that I use that actually brings me a lot of joy and comfort. It’s a word that in my community is very positive. But of course for some people it’s a ‘bad’ word, meaning it’s a word that was used to cause pain and hurt.”

In short: teach kids nuance now to help avoid adult shame and anxiety later.

4. “Secret Touching” (As Opposed to “Bad Touch”)

This is a term coined by Jan Hindman in her book A Very Touching Book, which Cory adopted in Sex Is a Funny Word, to talk about sexual abuse in a way that makes more sense for kids.

“The problem with using terms like ‘bad touch’ or ‘bad touching’ is that for some kids, their initial experience of sexual abuse won’t necessarily be that it feels bad. A lot of people who offend against children aren’t physically violent with them. For some kids the attention they are getting from an adult feels positive, or at least it’s the only attention they are getting.” Cory adds, ” Of course it isn’t positive, and even if there isn’t physical violence it is violence, and it is damaging.”

In the book, Cory writes to kids, “It’s called secret touching because no matter where someone touches you, or where you touch them, they make you keep it a secret.” When a child is being abused by someone they love or trust or respect, they may not want to get them in trouble by admitting the abuser has done something “bad.” The more nuanced language of “secret touching” can make it easier for children to open up about what we would call “abuse” but they often wouldn’t.

5. Justice

“Trust,” “joy” and “respect” are words that make multiple appearances throughout Sex Is a Funny Word, which many parents would find appropriate and self-explanatory. But another word that comes up again and again is “justice” — which is probably not the first word that comes to mind when most of us think about sexuality. So we asked Cory: When teaching kids about sex, “justice” might seem like a pretty distant, complicated, abstract term to throw into the mix of already difficult discussions — why is it important for kids to learn what it means in this context and how can parents introduce it seamlessly?

Cory’s response: “It’s important because sex, sexuality, and gender are always about more than biology and anatomy. When all we offer kids is information about how not to get pregnant and how not to get an STD we are only scratching the surface of what they need and of what sexuality is about.”

Cory asked us to imagine talking with a friend or partner about something sexually intimate and NOT talking about any of the following:

- your feelings

- your values

- where and how you were raised

- what you think makes a good or bad partner or spouse

It’s impossible! Point made.

Cory adds, “Including justice in a book about sex education for 7 to 10 year olds only seems strange to older kids and adults. I have yet to hear of any kid who has read the book and wondered why justice is in there. In my experience kids have a strong sense of justice, and they appreciate it being called out.”

Want more tips for talking with kids?

Read our interview with Cory about

What Makes a Baby

Yeah, I’m still not loving the word “vulva.” Language is dynamic, and if a word is commonly used to refer to something, at some point there’s a shift in its meaning. Millions of people use the word “vagina” to refer to the entirety of the female genitalia. At some point, the actual definition of the word shifts. I’d say we’re at that point.

Sure, a tiny minority is unhappy about that. It’s like Victorian grammarians shaking their walking sticks at people ending sentences in prepositions.

Anyway, when’s the last time you heard anyone remind their kid, “Make sure to wipe your anus!” You’d sound ridiculous (which is how “vulva” sounds to me and plenty of others). We use the words bum, or behind, or butt, or whatever–all of which refer to the entire ass. Is it medically precise? Nope. But it sure sounds better. (Just like saying “their kid” in the context above sounds better than “his or her,” despite the fact that the latter is technically more correct–though probably not for long.)

To better explain why getting it wrong matters, I turn to Joyce McFadden, psychologist, researcher and author of the book Your Daughter’s Bedroom: Insights for Raising Confident Women, who wrote the following in an article called “How Do We Influence the Women Our Daughters Become?“:

“If our little girls are raised to believe that boys have a penis but girls have a “down there,” we need to understand these girls will likely grow into women who, even in the new millennium, confuse their vulvas with their vaginas. Along the way, they’ll be at risk of seeing their bodies as the property of boys because they haven’t been supported in developing a sense of ownership over their own bodies, and this will put them at risk of unintended pregnancy as well as make them more susceptible to not knowing how to advocate for their safety in potentially dangerous situations. And ultimately, they’re more likely to end up in long-term relationships or marriages in which they’re sexually unhappy.”

I agree that language is dynamic, and should be when it helps make communication more precise, inclusive progressive and helpful. Using “them/they/their” as opposed to “he/him/his//she/her/hers” is the most elegant solution to sexist language that puts girls, women and trans people at a disadvantage — it turns traditional grammatical rules on their head for the greater social good. But perpetuating ignorance in kids by not teaching them the correct terminology now can make them less body confident, more ashamed, and more confused later. So in these cases, just because something is common, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t challenge it when a more accurate alternative will have better outcomes. (There was a time when “Indians” was the most popular, widely used, and accepted term for Native Americans — everyone knew what it meant — but people successfully pushed for the more accurate and less offensive “Native Americans” for the good of the country.)

My young son loves to talk about butts, in fact his favorite phrase right now is “butt cheeks” (which, come to think of it, is a pretty accurate term for what exactly he’s referring to). But while we do talk about bottoms and tushies in this house, when I’m teaching him how to properly wipe, he knows the hole the poop comes out of is called his anus — I’m sure I’ve even said at some point “Make sure to wipe your anus”! And it’s no big deal.

By correctly naming body parts and thus normalizing them for kids (in addition to whatever cutesie terms we might also like to use), chances are they’ll grow up to be more comfortable talking to their doctors about any genital/gastroenterological issues and to their partners about what does and doesn’t feel good in regard to specific parts; they’ll be more comfortable and feel less shame exploring their bodies on their own; they won’t be thrown for a loop should they read sex tips and manuals which use the accurate terms; and in the horrible case of abuse, they’ll be more likely to admit it and more capable of describing it.

For more on this topic, check out: https://www.emandlo.com/2012/08/vagina-vs-vulva-theres-a-b-f-difference/

I guess I can see both sides of this argument — on the one hand, I totally get how the accurate naming of body parts could help a girl own her own body and her own sexuality when she is older. But on the other hand… there is so much good stuff in this book, and so much of it is so so important, that it seems a shame to potentially alienate parents who just aren’t the kind of people who would ever use the word “vulva.” I’m thinking of my two sisters, for example, who would both laugh me out of the room if I suggested it… and yet they both have daughters and I know they’d both be open to a lot of what’s in this book. But I think that the language thing might throw them off to the point where I don’t know that they’d want to read the book or take the rest of its contents seriously (even though they should).

Well Mulva (ha!), the word “vulva” doesn’t make an appearance in the book until page 64, so just give it to them and they’ll be sold by the time they get there! Besides, the word “vagina” is on page 63, so that should make them feel better. Anyway, if you truly see the benefit for your kids of accurately naming body parts, then are you really going to deny them those benefits because you’re afraid your siblings will make fun of you? What grade are you in?

But this isn’t about saying “down there” for female genitalia, it’s about saying “vagina.” It’s no less specific (or more cutesy) a word than “penis” is if the meaning has evolved for the vast majority of people to signify the entirety of the genitalia. It’s just the word the vast, vast majority of people use. Sometimes language is just about communicating without being distracting.

See, for me, I wouldn’t tell my kids to wipe their “anus”–not because it’s a big deal, but because I want them to be able to communicate outside of my house in a way that’s not distracting to the listener. Most people refer to it as wiping their butt/ass/bottom/bum. “Anus” is more precise, but sounds ridiculous…to me that is. To each his/her own!